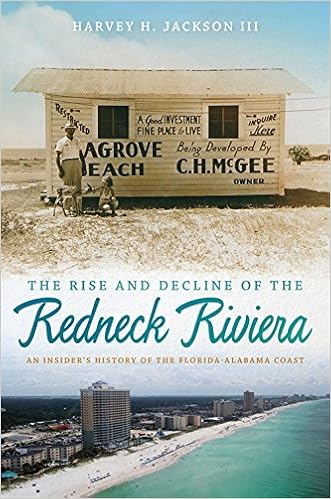

The Rise and Decline of the Redneck Riviera: An Insider's History of the Florida-Alabama Coast

Language: English

Pages: 352

ISBN: 0820345318

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

The Rise and Decline of the Redneck Riviera traces the development of the Florida-Alabama coast as a tourist destination from the late 1920s and early 1930s, when it was sparsely populated with “small fishing villages,” through to the tragic and devastating BP/Deepwater Horizon oil spill of 2010.

Harvey H. Jackson III focuses on the stretch of coast from Mobile Bay and Gulf Shores, Alabama, east to Panama City, Florida―an area known as the “Redneck Riviera.” Jackson explores the rise of this area as a vacation destination for the lower South’s middle- and working-class families following World War II, the building boom of the 1950s and 1960s, and the emergence of the Spring Break “season.” From the late sixties through 1979, severe hurricanes destroyed many small motels, cafes, bars, and early cottages that gave the small beach towns their essential character. A second building boom ensued in the 1980s dominated by high-rise condominiums and large resort hotels. Jackson traces the tensions surrounding the gentrification of the late 1980s and 1990s and the collapse of the housing market in 2008. While his major focus is on the social, cultural, and economic development, he also documents the environmental and financial impacts of natural disasters and the politics of beach access and dune and sea turtle protection.

The Rise and Decline of the Redneck Riviera is the culmination of sixteen years of research drawn from local newspapers, interviews, documentaries, community histories, and several scholarly studies that have addressed parts of this region’s history. From his 1950s-built family vacation cottage in Seagrove Beach, Florida, and on frequent trips to the Alabama coast, Jackson witnessed the changes that have come to the area and has recorded them in a personal, in-depth look at the history and culture of the coast.

A Friends Fund Publication.

appeals, the immediate effect was that at least one developer stopped developing. Down on the other end of Pleasure Island another controversy was brewing, and the mouse was about to find itself at the center of this one as well. Now there are few things that the folks who put the “redneck” in the Redneck Riviera valued more than their boats. Whether built for speed or fishing or both, whether used on the Intracoastal Waterway, taken back into the creeks and marshes, or powered out into the

before “Tea Party” protestors took to the streets and airwaves, there existed along the Redneck Riviera an attitude that held that the region had all the rules and regulations, government and governing that it needed—probably more—and that taxes were only one element in what many residents and visitors saw as a vast bureaucratic “conspiracy” to keep people from doing what they came to the beach to do. The warning was first raised when municipalities began to incorporate, and from that time

have down here is a cluster fuck. We want a plan with objectives and specific knowledge of what will be done to achieve those objectives. We want SOMEBODY to have the authority to make a decision in a matter of hours, not months. We’ve had enough meetings to make an academic administrator envious. Now go to work.” Going to work was what they were doing over in Destin. After the county commissioners voted to strike out alone if their plans got held up in red tape, the Florida Department of

as yet underappreciated and undeveloped. Without even a hamburger joint at which to hang out, local high school kids took their dates, a few blankets, and maybe a six pack or two out to Holiday Isle across the sound from the docks (everybody had a boat it seemed). There they built a fire and had a party. I have talked to a lot of adults who grew up on the coast and none would have wanted to be young anywhere else. Though the beaches grew and prospered, rural-based county leaders in Walton,

coastal communities, and in one particular instance a lack of foresight by the Orange Beach City council led to a decision regretted again and again. In the fall of 1999, the city fathers turned down a chance to purchase a twenty-six-acre plot that sat on both sides of the beach highway and included a stretch of undeveloped shoreline. They should have done it. Though the price was steep, $20.6 million, developers would later pay a lot more for it. And Orange Beach would be without its own beach.