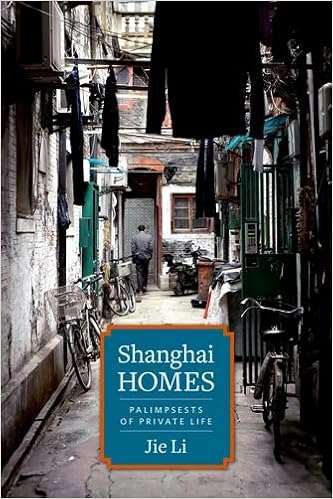

Shanghai Homes: Palimpsests of Private Life (Global Chinese Culture)

Jie Li

Language: English

Pages: 280

ISBN: 0231167172

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

In the dazzling global metropolis of Shanghai, what has it meant to call this city home? In this account―part microhistory, part memoir―Jie Li salvages intimate recollections by successive generations of inhabitants of two vibrant, culturally mixed Shanghai alleyways from the Republican, Maoist, and post-Mao eras. Exploring three dimensions of private life―territories, artifacts, and gossip―Li re-creates the sounds, smells, look, and feel of home over a tumultuous century.

First built by British and Japanese companies in 1915 and 1927, the two homes at the center of this narrative were located in an industrial part of the former "International Settlement." Before their recent demolition, they were nestled in Shanghai's labyrinthine alleyways, which housed more than half of the city's population from the Sino-Japanese War to the Cultural Revolution. Through interviews with her own family members as well as their neighbors, classmates, and co-workers, Li weaves a complex social tapestry reflecting the lived experiences of ordinary people struggling to absorb and adapt to major historical change. These voices include workers, intellectuals, Communists, Nationalists, foreigners, compradors, wives, concubines, and children who all fought for a foothold and haven in this city, witnessing spectacles so full of farce and pathos they could only be whispered as secret histories.

Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2007. ——. Shanghai on Strike: The Politics of Chinese Labor. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1993. Perry, Elizabeth J. and Li Xun. Proletarian Power: Shanghai in the Cultural Revolution. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1997. Prost, Antoine. “Public and Private Spheres in France.” In A History of Private Life, vol. 5: Riddles of Identity in Modern Times, edited by Antoine Prost and Gérard Vincent, 1–144. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press,

Campaign, 66–67; and Japanese presence in China, 44; labor reform in Shanghai suburbs, 68, 75, 101–102; leaving something for posterity, 211–212; loss of housing to children, 80–84, 133; and Mao Zedong’s portrait, 112; and No. 183, Pingliang Road, 4, 41, 47, 62, 68, 80–84, 82, 87, 88, 97, 209, 211–213; radios of, 109, 140; relationship with married children, 133–134; retiring to give job to Aunt Bean, 80; as Rightist, 66–70, 74, 75, 80, 81, 97, 98, 100, 112, 113, 114; and Three-Anti Five-Anti

with things—stools and boxes, pots and pans and basins. Private property placed in communal areas was often not worth very much to their owners, yet endless battles were fought over them. As Svetlana Boym writes of the Soviet communal apartment, “in circumstances of extreme overcrowdedness and imposed collectivity there is an extreme—almost obsessive—protection of minimal individual property.”64 In those days, every door and window, every drawer and cabinet were clamped with bolts and locks. One

nature’s cycles along with its gifts and threats of sun, rain, and wind. They collected the sun’s heat and dryness in their blankets to kill the mildew that built up over the rainy season. To save water they collected the rain to mop their wooden floors until they shined, or they recycled their face-washing water to wash their feet, their rice-washing water to wash the dishes, their laundry water to wash their night stools. To save electricity they turned on the light only when it got really

as an example, “with its own virtues, initiatives, and faults,”44 and constituted a different and perhaps more powerful kind of education than schools, mass media, and other ideological training grounds. Like grass growing out of stone cracks, these are stories of resilient survival in a world that did not allot these women proper places. These stories without redemptive endings briefly turn these shadowy figures and marginal characters into the protagonists of their own narratives, woven into