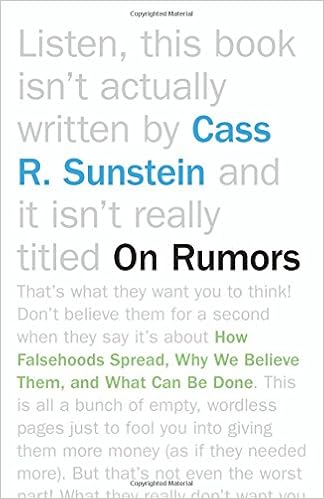

On Rumors: How Falsehoods Spread, Why We Believe Them, and What Can Be Done

Language: English

Pages: 128

ISBN: 0691162506

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

Many of us are being misled. Claiming to know dark secrets about public officials, hidden causes of the current economic situation, and nefarious plans and plots, those who spread rumors know precisely what they are doing. And in the era of social media and the Internet, they know a lot about how to manipulate the mechanics of false rumors--social cascades, group polarization, and biased assimilation. They also know that the presumed correctives--publishing balanced information, issuing corrections, and trusting the marketplace of ideas--do not always work. All of us are vulnerable.

In On Rumors, Cass Sunstein uses examples from the real world and from behavioral studies to explain why certain rumors spread like wildfire, what their consequences are, and what we can do to avoid being misled. In a new afterword, he revisits his arguments in light of his time working in the Obama administration.

asked to read a correction from either the New York Times or FoxNews.com. When they did so, the correction actually increased people’s commitment to the proposition in question. Presented with evidence that tax cuts do not increase government revenues, conservatives ended up with a commitment to this belief stronger than that of conservatives who did not read a correction. Or consider this question: does Obamacare create death panels? How do people answer this question? A careful study, with the

the president is not a communist spy. Suppose that the Sensibles read balanced materials on these three questions. To the Sensibles, the materials that support their original view will seem more than just convincing; they will also offer a range of details that, for most Sensibles, will fortify what they thought before. By contrast, the materials that contradict their original views will seem implausible, incoherent, ill-motivated, and probably a bit crazy. The result is that the original

principle imposes restrictions on Smith’s libel action too—a conclusion that has implications for what is said on Facebook, YouTube, and anywhere else. In Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc.,83 the Court ruled that people could recover damages for libel only if they could prove negligence. What this means is that if someone says something false and damaging about you, it is not enough that the statement was false and that you were badly harmed. You must also show that the speaker did not exercise proper

those involved in the political domain, the First Amendment imposes real restrictions. Courts have come close to saying that public figures essentially lose their ability to protect themselves against disclosure of private facts.86 If a blogger or a newspaper discloses some embarrassing or even humiliating truth about a governor or a senator, the Constitution protects its right to do so. • Insofar as we are dealing with the publication of private facts about ordinary people, the free speech

rumor that they are creating or spreading. One propagator will have terrific success in some worlds but none at all in others; another propagator will show a radically different pattern of success and failure. Quality, assessed in terms of correspondence to the truth, might not matter a great deal or even at all. Recall that on YouTube, cascades are common, as popular videos attract increasing attention not necessarily because they are good but because they are popular. Something similar happens