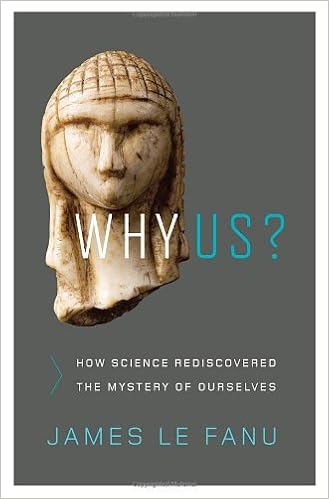

Why Us?: How Science Rediscovered the Mystery of Ourselves

James Le Fanu

Language: English

Pages: 320

ISBN: B005K5Y9MA

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

The triumph of science in explaining man’s unique place in the universe might seem almost complete. But in this lucid and compelling account, James Le Fanu describes how in the recent past science has come face-to-face with two seemingly unanswerable questions concerning the nature of genetic inheritance and the workings of the brain–questions that suggest there is, after all, “more than we can know.”

“Scientists do not ‘do’ wonder,” he writes in his introduction. “Rather . . . they have interpreted the world through the prism of supposing there is nothing in principle that cannot be accounted for.” But Le Fanu argues that there is nothing so full of wonder as life itself. As revealed by recent scientific research, it is simply not possible to get from the monotonous sequence of genes strung out along the double helix to the infinite beauty and diversity of the living world, or from the electrical activity of the brain to the richness and abundant creativity of the human mind. Le Fanu’s exploration of these mysteries, and his analysis of where they might lead us in our thinking about the nature and purpose of human existence, form the impassioned and riveting heart of Why Us?

Synthesis (Harvard University Press, 1975); E O Wilson, On Human Nature (Penguin, 1995; first published 1978) Page 166 – ‘Altruism ought to be non-existent…’ David Stove, Darwinian Fairy Tales (Avebury, 1995) Page 167 – While an undergraduate at Cambridge University… Marek Kohn (Faber & Faber, 2004), op. cit. Page 167 – Hamilton found a way to express this idea… W D Hamilton, ‘The Genetical Evolution of Social Behaviour’, Journal of Theoretical Biology, 1964, vol 7, pp 1–52 Page 169 –

staggeringly difficult to pull off, which is presumably why no other species has attempted it. Standing upright is, on reflection, a rather bizarre thing to do, and would seem to require a sudden and dramatic wholescale ‘redesign’ that is clearly incompatible with Darwin’s proposed mechanism of a gradualist evolutionary transformation. Lucy’s pivotal role in man’s evolutionary ascent as the beginning or anchor of that upward trajectory would seem highly ambiguous. These difficulties seem less

knowing, and life would not be worth living … I mean the intimate beauty which comes from the harmonious order of its parts and which a pure intelligence can grasp.’ The greatest (probably) of all scientists, Isaac Newton, seeking to comprehend that ‘harmonious order of parts’, would discover the fundamental laws of gravity and motion, that, being Universal (they hold throughout the universe), Absolute (unchallengeable), Eternal (holding for all time) and Omnipotent (all-powerful), he inferred,

would, over time, become enormously more sophisticated and complex, but the universe would still not become ‘knowable’ till the third and final event, the emergence of humans, with the faculty of language that permits them to think, and then to think about those thoughts and discuss their significance by inserting them into the minds of others gathered around the campfire. Thus, the arrival of our species, witnessed so eloquently by the wondrous art and technology of our earliest ancestors,

at the University of London, ‘the present one is rooted in the belief that an image of the visual world is actively constructed by the cortex.’ And why? The image-processing capacity of the eyes is far too limited to hope to reflect the prodigious subtlety and complexity of the world ‘out there’. Those limitations are familiar: the eyes themselves are in constant motion; the two images, not one, that they generate are distorted, turned upside down; and so on. Thus the only way we can ‘see’ is by