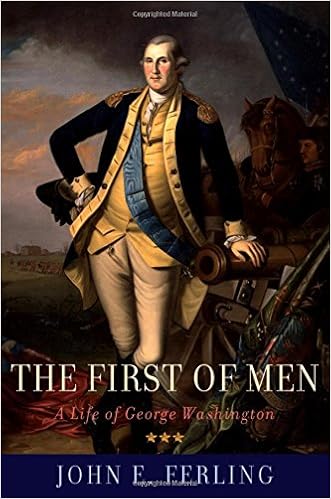

The First of Men: A Life of George Washington

John E. Ferling

Language: English

Pages: 616

ISBN: 019539867X

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

Written by John Ferling, one of America's leading historians of the Revolutionary era, The First of Men offers an illuminating portrait of George Washington's life, with emphasis on his military and political career.

Here is a riveting account that captures Washington in all his complexity, recounting not only Washington's familiar sterling qualities--courage, industry, ability to make difficult decisions, ceaseless striving for self-improvement, love of his family and loyalty to friends--but also his less well known character flaws. Indeed, as Ferling shows, Washington had to overcome many negative traits as he matured into a leader. The young Washington was accused of ingratitude and certain of his letters from this period read as if they were written by "a pompous martinet and a whining, petulant brat." As commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, he lost his temper more than once and indulged flatterers. Aaron Burr found him "a boring, colorless person." As president, he often believed the worst about individual officials. Ferling concludes that Washington's personality and temperament were those of "a self-centered and self-absorbed man, one who since youth had exhibited a fragile self-esteem." And yet he managed to realize virtually every grand design he ever conceived. Ferling's Washington is driven, fired by ambition, envy, and dreams of fame and fortune. Yet his leadership and character galvanized the American Revolution--probably no one else could have kept the war going until the master stroke at Yorktown--and helped the fledgling nation take, and survive, its first unsteady steps.

This superb paperback makes available once again an unflinchingly honest and compelling biography of the father of our country.

claim possession of Richmond. Shortly thereafter Arnold went into winter quarters, but his presence in Virginia compelled Washington to reconsider his options.3 Since late in November the principal American army in the South had belonged to Nathanael Greene. Appointed by Washington after Gate’s failure at Camden, Greene had taken command at Charlotte thirty days before Arnold’s landing in Virginia. Heavily outnumbered, Greene envisaged a war of posts, his army sustained by shipments of essential

dissipation, and corruption,” and that would procure “tranquility . . . safety . . . prosperity . . . Liberty.” The America he envisioned would become a “fortress,” a “Palladium of your political safety and prosperity.” Great Britain, however, held the key to the rapid fulfillment of Washington’s dreams. It was as though he could never escape the tentacles of that empire. Frustrated in his youthful ambitions by imperial officials, he had watched in continued frustration after 1783 as America was

preparedness campaign. In fact, when Hamilton, who feared that southern Democratic-Republicans would never support a war with France, urged him to make a tour of the region to rally the populace for hostilities, the ex-president rejected the suggestion. He feared the “malicious insinuations” that such activity would elicit, he said. He added, too, that he doubted that a land war with France would occur. A naval war, perhaps, but he could not believe that France would invade America, though their

himself with the cantonment of this or that unit and with various appointments. But there was little glory in what he did, and surely there was less glamour to his role than he must have anticipated when he had “consented to Gird on the Sword.” For a time it must have seemed to him that the design of his uniform was his most pressing concern.48 In fact, his letters soon betrayed his realization that he was little but a figurehead general; “my opinions and inclinations are not consulted,” he

extinction. Given the army’s chronic supply shortages, few men were likely to reenlist. If the legion’s troubles were not soon rectified, he added, “the Army must absolutely break up.”43 Congress had heard these complaints since July, although to this point it had only coped with the problem of the powder shortage. Approximately fifteen tons of powder had been procured from New York and Pennsylvania and shipped to the army, and at Congress’s urging Rhode Island provided Washington with an