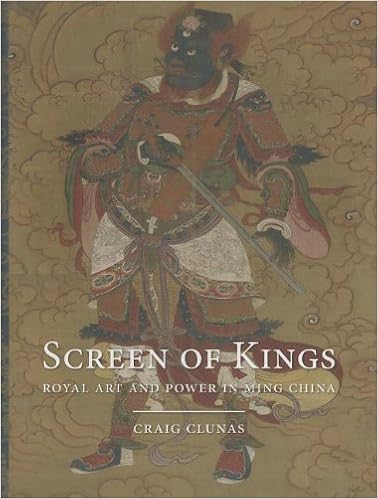

Screen of Kings: Royal Art and Power in Ming China

Craig Clunas

Language: English

Pages: 232

ISBN: 0824838521

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

Screen of Kings is the first book in any language to examine the cultural role of the regional aristocracy – relatives of the emperors – in Ming dynasty China (1368–1644). Through an analysis of their patronage of architecture, calligraphy, painting and other art forms, and through a study of the contents of their splendid and recently excavated tombs, this innovative study puts the aristocracy back at the heart of accounts of China’s culture, from which they have been excluded until very recently.

Screen of Kings challenges much of the received wisdom about Ming China. Craig Clunas sheds new light on many familiar artworks, as well as works that have never before been reproduced. New archaeological discoveries have furnished the author with evidence of the lavish and spectacular lifestyles of these provincial princes and demonstrate how central the imperial family was to the high culture of the Ming era.

Written by the leading specialist in the art and culture of the Ming period, this book illuminates a key aspect of China’s past, and will significantly alter our understanding of the Ming. It will be enjoyed by anyone with a serious interest in the history and art of this great civilization.

patronage was expressed through a religious complex which survives in only fragmentary form, but which is still impressive enough to give some sense of its scale and magnificence before it was badly damaged by fire in 1864, further vandalized in the upheavals of the Cultural Revolution, and reduced to the still imposing fragment which is one of the major monuments of Taiyuan today. This is the Chongshansi (‘Temple of the Veneration of Goodness’, illus. 3), a Buddhist site built in the 1390s by

documentation, ascribed to an unidentified fifteenth-century ‘Prince of Heng’, sold from the collection of the great Dutch sinologist Robert van Gulik (1910–1967) in 1983.18 The piece is roughly 1 metre square, and the text is 68 a poem by the Tang dynasty poet Liu Yuxi (772–842), the sort of calligraphic exercise which existed in large numbers in the Ming period, often designed to be given as gifts or marks of favour by superiors. It is not possible from the information surviving to identify

He once painted several scrolls of Sichuan sunflowers and exposed them to the sun, and bees and butterflies congregated on the flowers, when brushed off they kept coming. The King of Hengyang was excellent at painting eagles. The King of Yongning was excellent at painting peonies. King Jing of Ning, Dianpei, his hao was ‘Lazy Immortal of the Bamboo Grove’, and he was the grandson of King Xian of Ning. He sketched landscapes and plants which were natural, divine and marvellous. The King of

created or owned, slipped from our view. One possible way of guarding against the loss of important images is their reproduction, and just as with calligraphy it seems that kingly households were involved in this activity. Yet 131 screen of kings 59 Detail of procession of goddesses, from murals dated 1515 from the eaves of the Shengmudian (‘Hall of the Holy Mother’), Jinci, Taiyuan, Shanxi province. again there is an intriguing analogy between biological reproduction and cultural

on an auspicious day of the 5th month, made in the Seals Office (Dian bao suo) of the Kingdom of Yi, a pearl crown mounted with gold phoenixes, each calculated at a weight of 2 liang, 2 qian and 8 fen exactly.53 One of the mirrors in this tomb also carries an inscription stating it was a product of the same workshop. Yet the interplay of local and central is underlined by the presence in this tomb also of items which are clearly gifts from the imperial court. In this case they are bolts of white