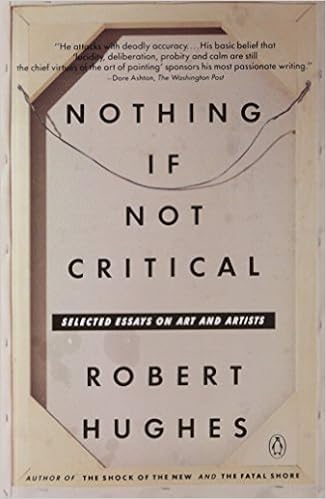

Nothing If Not Critical: Selected Essays on Art and Artists

Robert Hughes

Language: English

Pages: 448

ISBN: 014016524X

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

From Holbein to Hockney, from Norman Rockwell to Pablo Picasso, from sixteenth-century Rome to 1980s SoHo, Robert Hughes looks with love, loathing, warmth, wit and authority at a wide range of art and artists, good, bad, past and present.

As art critic for Time magazine, internationally acclaimed for his study of modern art, The Shock of the New, he is perhaps America’s most widely read and admired writer on art. In this book: nearly a hundred of his finest essays on the subject.

For the realism of Thomas Eakins to the Soviet satirists Komar and Melamid, from Watteau to Willem de Kooning to Susan Rothenberg, here is Hughes—astute, vivid and uninhibited—on dozens of famous and not-so-famous artists. He observes that Caravaggio was “one of the hinges of art history; there was art before him and art after him, and they were not the same”; he remarks that Julian Schnabel’s “work is to painting what Stallone’s is to acting”; he calls John Constable’s Wivenhoe Park “almost the last word on Eden-as-Property”; he notes how “distorted traces of [Jackson] Pollock lie like genes in art-world careers that, one might have thought, had nothing to do with his.” He knows how Norman Rockwell made a chicken stand still long enough to be painted, and what Degas said about success (some kinds are indistinguishable from panic).

Phrasemaker par excellence, Hughes is at the same time an incisive and profound critic, not only of particular artists, but also of the social context in which art exists and is traded. His fresh perceptions of such figures as Andy Warhol and the French writer Jean Baudrillard are matched in brilliance by his pungent discussions of the art market—its inflated prices and reputations, its damage to the public domain of culture. There is a superb essay on Bernard Berenson, and another on the strange, tangled case of the Mark Rothko estate. And as a finale, Hughes gives us “The SoHoiad,” the mock-epic satire that so amused and annoyed the art world in the mid-1980s.

A meteor of a book that enlightens, startles, stimulates and entertains.

their pictorial meanings. Gorky had a lyrical sense of natural life, expressed always as the close-up or interior view rather than the landscape with figures. Filled with a sweating, preconscious glow, images such as The Liver Is the Cock’s Comb look inward to the body and not out from it. At the same time, the best Gorkys are delicate, almost hesitant, in their pictorial means (especially in the wayward slicing of that black line across the surface), which makes the theatricality of some of his

itself more vividly than in his transactions (or lack of them) with the culture of his time, modernism. For an art writer to have lived through one of the supreme periods in Western art history, the forty years from 1890 to 1930, and not to have uttered one intelligent syllable about it is nothing to be proud of, but Berenson managed to do it. Often he seemed to have no idea of what was going on around him. He not only anathematized Pound, Joyce, Stein, Eliot and especially Freud. He actually

marks the 1980s, it is no wonder that the spectacle of privilege enjoying its own toilette has become America’s hottest cultural ticket. Thus Lord Marchmain of Brideshead becomes the Blake Carrington of the American upper-middle classes. Museums have learned their part in this vicarious regilding. They supply a sense of history as spectacle. This seems to mesh particularly nicely, of course, with the English-heritage industry. Relatively few Americans can imagine themselves as King Tut, Rudolf

wanted to go back before Raphael, appealing to a moment in history—the Middle Ages on the cusp, as it were, of the Renaissance—when art seemed not to be entangled in false ideals and academic systems. Their bywords were purge, simplify, archaize. Like all true cultural revolutionaries, they were conservatives at heart, and they were lucky in having as their megaphone and mentor the greatest art critic ever to use the English language: John Ruskin. They needed whatever friends they had. The

a porch for what one would now call a photo opportunity. But it happened that Henry Luce was looking for an uplifting, patriotic circulation-builder for the Christmas 1934 issue of Time. Maynard Walker was duly interviewed, Thomas Hart Benton’s self-portrait went on the cover, and American Regionalism was born. “A play was written and a stage erected for us,” Benton would later remark. “Grant Wood became the typical Iowa small towner, John Curry the typical Kansas farmer, and I just an Ozark