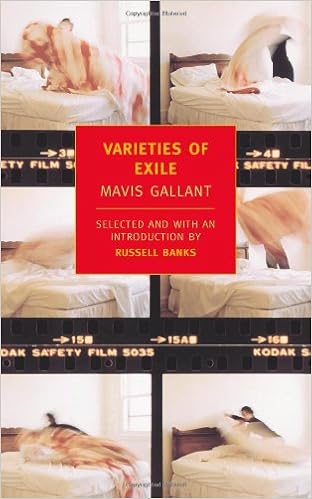

Varieties of Exile (New York Review Books Classics Series)

Language: English

Pages: 344

ISBN: 1590170601

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

Mavis Gallant is the modern master of what Henry James called the international story, the fine-grained evocation of the quandaries of people who must make their way in the world without any place to call their own. The irreducible complexity of the very idea of home is especially at issue in the stories Gallant has written about Montreal, where she was born, although she has lived in Paris for more than half a century.

Varieties of Exile, Russell Banks's extensive new selection from Gallant's work, demonstrates anew the remarkable reach of this writer's singular art. Among its contents are three previously uncollected stories, as well as the celebrated semi-autobiographical sequence about Linnet Muir—stories that are wise, funny, and full of insight into the perils and promise of growing up and breaking loose.

father had in front of him a ledger of printed forms. He filled in the blank spaces by hand, using a pen, which he dipped with care in black ink. Mr. Fenton dictated the facts. Before giving the child’s name or its date of birth, he identified his wife and, of course, himself: They were Louise Marjorie Clopstock and Boyd Markham Forrest Fenton. He was one of those Anglos with no Christian name, just a string of surnames. Ray lifted the pen over the most important entry. He peered up,

which wasn’t a Montreal regiment—he couldn’t do anything like other people, couldn’t even join up like anyone else—and after the war he just chose to go his own way. I saw him downtown in Montreal one time after the war. I was around twelve, delivering prescriptions for a drugstore. I knew him before he knew me. He looked the way he had always managed to look, as if he had all the time in the world. His mouth was drawn in, like an old woman’s, but he still had his coal-black hair. I wish we had

then.” “No, thanks,” my father said. “No screen. Thanks all the same.” We had one more conversation after that. I’ve already said there were always women slopping around in the ward, in felt slippers, and bathrobes stained with medicine and tea. I came in and found one—quite young, this one was—combing my father’s hair. He could hardly lift his head from the pillow, and still she thought he was interesting. I thought, Kenny should see this. “She’s been telling me,” my father gasped when the

daughter of Sarah Bernhardt and a stork, is only a shadow, a tracing, with long arms and legs and one of those slightly puggy faces with pulled-up eyes. Her voice remains—the husky Virginia-tobacco whisper I associate with so many women of that generation, my parents’ friends; it must have come of age in English Montreal around 1920, when girls began to cut their hair and to smoke. In middle life the voice would slide from low to harsh, and develop a chronic cough. For the moment it was

been in, investigating a rumor. Marie told about the plant. He made her repeat the story twice, then said she had built up a reserve of static by standing on a shag rug with her boots on. She was not properly grounded when she approached the flower. “Raymond could have done more with his life,” said Marie, hanging up. Berthe, who was still awake, thought he had done all he could, given his brains and character. She did not say so: She never mentioned her nephew, never asked about his health. He