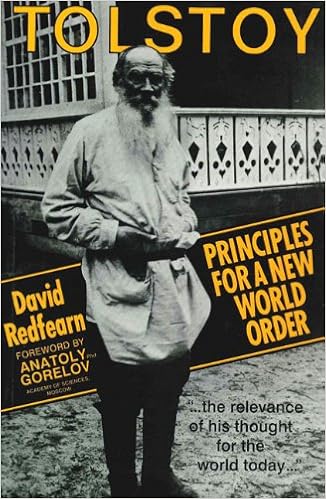

Tolstoy: Principles New World Order

Language: English

Pages: 192

ISBN: 0856831344

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

Biographers have hailed Leo Tolstoy as a literary giant but have misunderstood or misrepresented what he regarded as his most important work, namely his attempt to formulate a consistent philosophy which took its inspiration from the Sermon on the Mount but addressed itself to the political and economic problems of the day. This is the first comprehensive treatment of this endeavour which occupied the last 30 years of his life. David Redfearn explains how Tolstoy came to realize that the state existed to protect and preserve the privileges of the few and that the Church connived at the situation. As the truth of this became more and more obvious to him, he abandoned his literary career and set out to explore the true meaning of Christianity and to devise a system for securing economic justice. Redfearn points out that this endeavour took many years and in the process Tolstoy went down a number of blind alleys, thus giving rise to inconsistencies. His own position as one of the privileged class exacerbated the situation, because he was torn between his desire to practice his philosophy and his duty to his family. It is therefore on his mature philosophy that this part of his life should be judged. One of the great influences of his life, one which helped him clarify his economic thinking, was the work of his contemporary, the American social reformer Henry George. He was so impressed that in 1902 he urged the Tsar to introduce the tax and land tenure reforms advocated by George - to no avail. The full text of his letter is reproduced in the book. In his foreword Dr. Gorelov reveals that Tolstoy's later works are once more being studied by reformers in Russia seeking an alternative social philosophy to Marxism and capitalism. David Redfearn argues that Tolstoy's work is equally relevant to the industrialised West and the Third World for it was essentially a critique of the capitalist system.

lodged a formal complaint with the courts. Both the governor and the public prosecutor assured Tolstoy that the peasants were in the right; but, despite this, the judge who first heard the case decided in favour of the landowner. All the higher courts, including the Senate, confirmed this decision; so the landowner ordered the felling of trees to be resumed. The peasants, however, unable to accept that the law could be manipulated in this unjust manner, refused to submit, and drove away the men

elucidate the land question. God needs such labourers as much as he does men of a wider sweep of perception. 1 It will probably now never be known whether this particular conversation was being conducted in Russian or in English; for each had a more than adequate knowledge of the other's language. In either case, Tolstoy's attitude to manual work makes it highly unlikely that the word 'labourers' or its Russian equivalent was intended to convey any pejorative meaning rather the contrary. The

mainly of his own corrupt and long-standing autocratic régime, George was a citizen of the United States of America, writing not much more than a hundred years later than the Declaration of Independence. He was conscious of corruption indeed, but had some residual faith in the processes of representative government. James Bonar might have tolerated state ownership of monopolies; but that is evidently where he would have drawn the line: If the ideal of state socialism be viewed in an equally

significant effect. Much more dramatic have been the results of land value taxation related to a specific type of expenditure in California, where the state legislature determined, in 1887, to create Irrigation Districts, so financed, for the purpose of retaining and distributing water during the rainless summer months. The result was the replacement of large, semi-desert areas, exploited only by the cattle barons, with small holdings of which the typical size is about 30 acres. N o further state

opinion exists, and even the habit of appointing to posts which require the greatest gifts and intelligence all sorts of Ivanovs, Petrovs, Zengers, Pleves etc., whose only virtue is that they are no different from other people. That's the first point. The second point is that it seems to me - and I regret it very much - that you haven't read and don't know the essence of George's project. The peasant class will not only not oppose the realisation of this project, but will welcome it as the