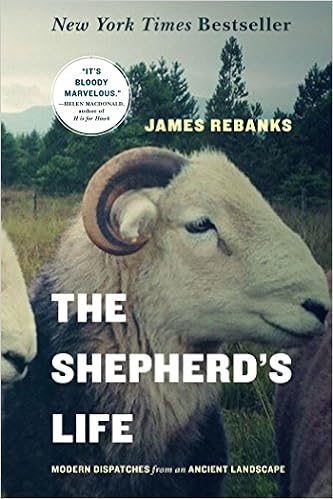

The Shepherd's Life: Modern Dispatches from an Ancient Landscape

Language: English

Pages: 304

ISBN: 1250060265

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

A major new talent redefines the literature of rural life.

Old world met new when a shepherd in the English Lake District impulsively started a Twitter account. A routine cell phone upgrade left author James Rebanks with a pretty decent camera and a pre-loaded Twitter app--the tools to share his way of life with the world. And what began as a tentative experiment became an international phenomenon.

James has worked the land for years, as did his father, and his father before him. His family has lived and farmed in the Lake District of Northern England as long as there have been written records (since 1420) and possibly much longer. And while the land itself has inspired great poets and authors we have rarely heard from the people who tend it. One Twitter account has changed all that, and now James Rebanks has broken free of the 140-character limit and produced "the book I have wanted to write my whole life.""The Shepherd's Life "is a memoir about growing up amidst a magical, storied landscape, of coming of age in the 1980s and 1990s among hills that seem timeless, and yet suffused with history. Broken into the four seasons, the book chronicles the author's daily experiences at work with his flock and brings alive his family and their ancient way of life, which at times can seem irreconcilable with the modern world.

An astonishing original work, "The Shepherd's Life" is an intimate look from inside a seemingly ordinary life, one that celebrates the meaning of place, the ties of family to the land around them, and the beauty of the past. It is the untold story of the Lake District, of a people who exist and endure out of sight in the midst of the most iconic literary landscape in the world.

"From the Hardcover edition.""

all at one time or another. He passed on stories inherited from his own grandfather that spanned back and forth across vast periods of time as if the 1850s or 1910 were yesterday. The ‘silver’ and ‘brass’ my grandmother polished included things brought home by soldiers in the family from the Boer and Crimean Wars. Granddad could read and write, and everyone in our world thought he was smart, but there was only one book in his house and it was about horse ailments. It’s fairly safe to assume he

of a grandchild, but it felt like she enjoyed the fighting. I felt it, despite the words. Sometimes it looked like hatred, sometimes just like love. They had been through a lot together and had had a ‘good life’, albeit full of troubles and incidents. When I worshipped him, he was getting old, and frustrated that old age was beating him. But he was still full of mischief. Theirs had been a shotgun marriage, and not the only one in our family judging by the dates of first-born children in our

doffed his cap to no man. No one told him what to do. He lived a modest life but was proud and free and independent, with a presence that said he belonged in this place in the world. My first memories are of him, and knowing I wanted to be just like him some day. We live and work our small hill farm in the far north-west of England, in the Lake District. We farm in a valley called Matterdale, between the first two rounded fells (mountains) that emerge on your left as you travel west on the main

change that because I was there when they were born and when they lambed, and I was home to help clip many of them. Occasionally, one eludes our memories and we have to check its ear tag and Dad’s scruffy old notepad, but a moment later Dad shouts out in triumph, ‘It’s out of that Geoff Marwood ewe I bought. I should have known her, put her to the big Ewbank tup.’ My grandfather used to have an anecdote for every ewe, and used to drive us mad telling us where each one lambed, what its lamb sold

maybe fifteen farms. It might take ten days to cover the whole breed area, so different inspectors do a day each, generally. Endless debates take place about whether the inspectors are consistent on any given issue. Like football referees, their judgement is scrutinized and not always respected. I’m on the third or fourth floor of a building just off Oxford Street in London. I left the flat in Oxford at 5.30 a.m. to catch a train, and won’t get home until 10 p.m. My work cubicle is about three