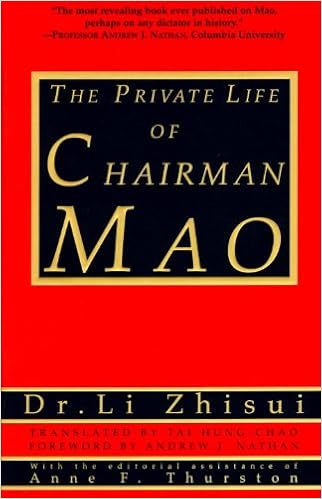

The Private Life of Chairman Mao

Li Zhisui

Language: English

Pages: 736

ISBN: 0679764437

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

From 1954 until Mao Zedong's death 22 years later. Dr. Li Zhisui was the Chinese ruler's personal physician. For most of these years, Mao was in excellent health; thus he and the doctor had time to discuss political and personal matters. Dr. Li recorded many of these conversations in his diaries, as well as in his memory. In this book, Dr. Li vividly reconstructs his extraordinary time with Chairman Mao. of illustrations.

to be there. It was my first visit to Chengdu since graduating from medical school some fourteen years before, and the city was my second home. I visited my old university as soon as I could. The campus of West China Union University Medical School had also been a lush botanical garden, the biggest and prettiest in China, and when I was a student, it had been my paradise on earth. But everything had changed. A large road had been built through the old campus, and many buildings had been

interrupted. “The Chairman just eats till he’s full and has nothing else to do,” Ye complained. “What the fart good can this trip of ours do?” I insisted we had to go. The Chairman wanted us to investigate. “You go tell Huang Shuze about it,” he said. “Then we’ll get together and talk about it. But we can’t leave tomorrow. I need a few days.” His talk was making me nervous. We could not delay. “Chairman asked us to leave tomorrow,” I insisted. “We can’t refuse his orders.” I suggested that Ye

landlord’s son and was invariably assigned the hardest and heaviest jobs. He worked without a word of complaint. But the man, in fact, was not a landlord’s son. He had been born into one of the village’s poorest families, and his impoverished parents, in order to save him, had given him in adoption to a landlord. For that, he had been labeled the son of a landlord, forced to work as a coolie, deprived of all rights, and was at the beck and call of the village leaders. Among the impoverished

why Hai Rui and Wu Han were under attack. I certainly had no idea that Yao Wenyuan’s article was the opening salvo of what was about to become Mao’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Nor did I fully understand to whom Mao was referring when he said that “they” were awfully tough. Only after the Cultural Revolution began did I understand that “they” included head of state Liu Shaoqi and all the top leaders most closely associated with him. I remained silent. I needed to understand Mao’s

Hospital, and his colleague Li Chunfu, the director of the ear, nose, and throat department there, joined us to discuss the effects of paralysis of the throat and pharnyx and to work out procedures for dealing with that problem. The doctors agreed with what was widely known: that the only way to prevent food or liquid from entering the trachea was to feed Mao through a nasal tube. Zhang Yuanchang, the Shanghai neurologist, was particularly concerned about paralysis of the intercostal muscles,