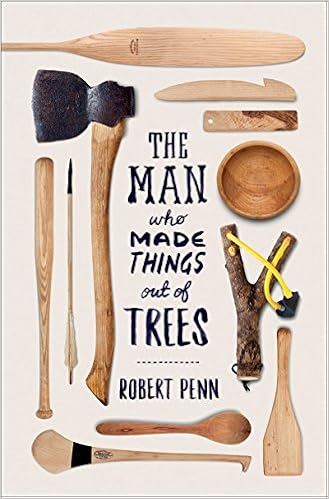

The Man Who Made Things Out of Trees

Robert Penn

Language: English

Pages: 256

ISBN: 0393253732

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

The story of how one man cut down a single tree to see how many things could be made from it.

Out of all the trees in the world, the ash is most closely bound up with who we are: the tree we have made the greatest and most varied use of over the course of human history. One frigid winter morning, Robert Penn lovingly selected an ash tree and cut it down. He wanted to see how many beautiful, handmade objects could be made from it.

Thus begins an adventure of craftsmanship and discovery. Penn visits the shops of modern-day woodworkers―whose expertise has been handed down through generations―and finds that ancient woodworking techniques are far from dead. He introduces artisans who create a flawless axe handle, a rugged and true wagon wheel, a deadly bow and arrow, an Olympic-grade toboggan, and many other handmade objects using their knowledge of ash’s unique properties. Penn connects our daily lives back to the natural woodlands that once dominated our landscapes.

Throughout his travels―from his home in Wales, across Europe, and America―Penn makes a case for the continued and better use of the ash tree as a sustainable resource and reveals some of the dire threats to our ash trees. The emerald ash borer, a voracious and destructive beetle, has killed tens of millions of ash trees across North America since 2002. Unless we are prepared to act now and better value our trees, Penn argues, the ash tree and its many magnificent contributions to mankind will become a thing of the past. This exuberant tale of nature, human ingenuity, and the pleasure of making things by hand chronicles how the urge to understand and appreciate trees still runs through us all like grain through wood.

8 pages of illustrations

felled, I had waited several weeks for the haulier to show up. There were then further, unexpected delays at the sawmill and it was the end of spring when the trunk was finally sawn into boards. ‘Stacking your timber to dry at this time of year is far from ideal, but you might just get away with it,’ Will Bullough at Whitney Sawmills had said. ‘Keep your fingers crossed we have a cold, damp start to the summer.’ Two days later, a heatwave began. On instructions from Will, I stacked my tree (or

branches below the living crown of the tree. For the creative woodworker, however, knots and other irregularities of nature can be valuable features: they can form the heart of beautiful craftsmanship and art, even if they do cause problems. Robin had skilfully worked around the knot encased in my piece of ash branch wood. He had managed to convert a problem into a feature, enhancing the natural element and the beauty of the bowl. He looked content in his work again. There was another ‘tch-ock’

and wood was, again, central to that story. Timber barons, railroad trusts and mining companies mowed down vast swathes of mature timber to feed the nation’s hunger for wood products like housing, railroad sleepers or ties, pit props and fuel. The scientist and ‘Father of the U. S. Weather Service’, Increase Lapham, noted in 1867: ‘Without the fuel, the buildings, the fences, furniture … utensils and machines of every kind, the principal materials of which are taken directly from the forests, we

Agriculture (USDA) report, federal and state agencies had already spent $209 million trying to control the beetle’s impact. The beetle has more recently been identified in Russia, east of Moscow. It seems inevitable that it will reach Europe, probably before 2025. Predictions are difficult, but it is reasonable to assume that the populations of ash in both Europe and North America, along with a wide array of biodiversity that depends on the species, will continue to be devastated over the next

decay, it provides sanctuary and sustenance to an evolving legion of wildlife species: insects, fungi, mosses, lichens, invertebrates and small mammals. In fact, some species can only live in deadwood. The rule of thumb, at least for conservation-minded woodmen, is to leave one quarter of a tree for the benefit of the woodland, where it will rot along with the fallen leaves and eventually return to the earth as humus. Decades from now, that humus will encourage ash seeds to become saplings, in