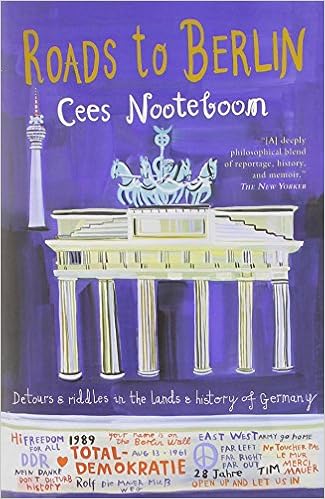

Roads to Berlin

Cees Nooteboom

Language: English

Pages: 400

ISBN: 1623658446

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

The winner of numerous literary awards including the Anne Frank Prize and Goethe Prize, Cees Nooteboom, novelist, poet and journalist, "is a careful prose stylist of a notably philosophical bent." (J.M. Coetzee, The New York Review of Books)

In Roads to Berlin, Nooteboom's reportage, "from a 1963 Khrushchev rally in East Berlin to the tearing down of the Palast der Republik, brilliantly captures the intensity of the capital and its â??associated layers of memory,'" The Economist said. The book maps the changing landscape of post-World-War-II Germany, from the period before the fall of the Berlin Wall to the present. Written and updated over the course of several decades, an eyewitness account of the pivotal events of 1989 gives way to a perceptive appreciation of its difficult passage to reunification. Nooteboom's writings on politics, people, architecture, and culture are as digressive as they are eloquent; his innate curiosity takes him through the landscapes of Heine and Goethe, steeped in Romanticism and mythology, and to Germany's baroque cities. With an outsider's objectivity he has crafted an intimate portrait of the country to its present day.

From the Hardcover edition.

through the border checkpoint so many times, and later I see the ruins of the Palast der Republik. Now that it is no longer there, it seems as though it was much larger than I actually remember. The stairwells are still standing, on this autumn day, towers of steps surrounded by cranes and bulldozers, the demolished church of a forgotten religion, ridiculed by the mighty shadow of the Dom behind, with its triumphant golden cap. There is something unutterably sad about buildings that have not yet

line for their “welcome money.”1 Old people with dazed expressions, in this part of the city for the first time in thirty years, come in search of their memories; young people who were born after the Wall went up, and who live maybe a kilometer away, walk around in a world they have never known, so ecstatic that the asphalt can barely hold them. As I write these words, church bells are ringing out on all sides, as they did a few days ago when the bells of the Gedächtniskirche suddenly pealed out

“always,” was expressed as “the whole time,” as if you could really say that about something that was not yet complete. Human time, scientific time, Newton’s time, which progressed uniformly and without reference to any external object; Einstein’s time, which allowed itself to be bewitched by space. And then the time of those infinitesimally tiny particles, pulverized, immeasurable diminution. He looked at the other people moving so solidly around him on Neuhauser Straße, each with their own

side. I tried to imagine these two districts snuggling up together, but I could not. It was too much of a challenge. First the towers would have to go, and those walls, and that sand, and new things would have to come, things I could not yet see. I knew that something would fill that space, but I did not know how. I am not a town planner; my task is documentation. Falkplatz, East Berlin, April 1990 And that is why I have now returned to that place, a different now, two weeks later, and why

which is more distant, more exotic for him, as he comes from the coast. They stop in Lindow, have something to eat at the Hotel Klosterblick, gaze out over the water, which looks cold and wintery, and decide that they would like to stay there or come back just to read and let the wind blow the world away from their minds. An old monastery wall, a few graves. What was it that his friend had said as they drove over the now invisible border? “The German that the border guards used to speak . . .