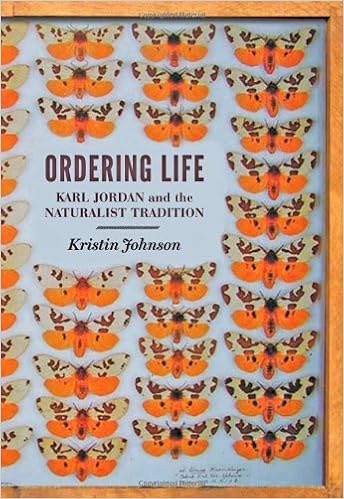

Ordering Life: Karl Jordan and the Naturalist Tradition

Kristin Johnson

Language: English

Pages: 392

ISBN: 1421406004

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

For centuries naturalists have endeavored to name, order, and explain biological diversity. Karl Jordan (1861–1959) dedicated his long life to this effort, describing thousands of new species in the process. Ordering Life explores the career of this prominent figure as he worked to ensure a continued role for natural history museums and the field of taxonomy in the rapidly changing world of twentieth-century science.

Jordan made an effort to both practice good taxonomy and secure status and patronage in a world that would soon be transformed by wars and economic and political upheaval. Kristin Johnson traces his response to these changes and shows that creating scientific knowledge about the natural world depends on much more than just good method or robust theory. The broader social context in which scientists work is just as important to the project of naming, describing, classifying, and, ultimately, explaining life.

The backlog of undescribed species sitting in the halls of large museums provided enough to keep curators and specialists busy, but, at least by Tring standards, the description of new species ideally proceeded in concert with the directed accumulation of new material by which conclusions could be tested. Horn’s imaginary mathematician’s calculation assumed that specimens arrived from every possible place according to taxonomists’ wishes, and that taxonomists—or someone—could pay for those

frontiers of Czechoslovakia and then Poland. Like many Germans traumatized by their nation’s postwar decline, some naturalists saw in the rise of the National Socialists enormous prospects for not only stability and prosperity but a return to the scientific glory of the prewar period. In the aftermath of the Great War, German naturalists, including Ernst Mayr, had often sought patronage elsewhere, since institutions such as the Berlin Zoological Museum had limited funds for specimens, much less

entomology, or the chaotic diversity of his fellow entomologists and their long legacy of “species-making.” On the other hand, each of these challenges inspired creative organizational efforts, eloquent manifestos, and careful reassessments of the aims and methods of entomological taxonomy as a whole. Jordan himself expressed a rather tempered view of his accomplishments. Miriam Rothschild recounted to Mayr how, as he finished reading Mayr’s contribution to the Festschrift, Jordan exclaimed,

See Mark Barrow, A Passion for Birds: American Ornithology after Audubon (Princeton University Press, 1998) and Erwin Stresemann’s classic Ornithology: From Aristotle to the Present (Harvard University, 1975). A few studies have been done on entrepreneurial natural history in the nineteenth century. See Barrow, “The Specimen Dealer: Entrepreneurial Natural History in America’s Gilded Age,” in the Journal for the History of Biology 33 (2000): 493–534 and Kohlstedt, “Henry A. Ward: The Merchant

those who had “given up the net to take their share in the terrible European struggle,” including more than a dozen men from the British Museum’s Entomological Department. Inevitably, the effort to improve the quality and quantity of entomologists’ concreta soon suffered as a result. During his presidential address for 1914, G. T. Bethune-Baker noted he had expected to have more specimens to back up his conclusions, “but alas, the war entirely upset these arrangements, and now some of my friends