Lud-in-the-Mist

Language: English

Pages: 230

ISBN: 1434442179

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

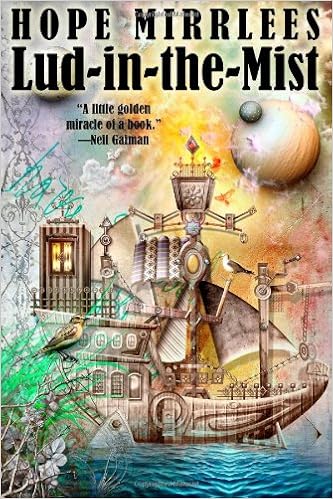

"The single most beautiful, solid, unearthly, and unjustifiably forgotten novel of the twentieth century ... a little golden miracle of a book."--Neal Gaiman Hope Mirrlees penned "Lud-in-the-Mist"--a classic fantasy, and her only fantasy novel--in 1926. When the town of Lud severs its ties to a Faerie land, an illegal trade in fairy fruit develops. But eating the fruit has horrible and wondrous effects. "Helen Hope Mirrlees was born in England in 1887. Mirrlees was a close friend of such literary lights as Walter de la Mare, T.S. Eliot, André Gide, Katharine Mansfield, Lady Ottoline Morrell, Bertrand Russell, Gertrude Stein, Virginia Woolf, and William Butler Yeats. Under her own name, she published three novels: Madeleine -- One of Life's Jansenists (1921); The Counterplot (1924); and her 1926 classic fantasy Lud-in-the-Mist, which has acknowledged inspiration to the likes of Neil Gaiman, Mary Gentle, Elizabeth Hand, Johanna Russ, and Tim Powers."--SF Site "Hope Mirrlees' writing, usually underrated, moves between gently crazy humour, poetic snatches, real menace, and real poignancy."--The Encyclopedia of Fantasy

Miss Primrose was a most accomplished needle-woman. “But what’s the good of needlework? It doesn’t teach one common sense,” he muttered impatiently. “And how like a woman!” he added with a contemptuous little snort, “Aren’t red strawberries good enough for her? Trying to improve on nature with her stupid fancies and her purple strawberries!” But he was in no mood for wasting his time and attention on a half-embroidered slipper, and tossing it impatiently away he was about to march out of the

sitting in, and following his son’s every movement with a sly, legal smile. No, there had certainly been nothing fantastic about Master Josiah. And yet … there was something not altogether human about these bright bird-like eyes and that very pointed chin. Had Master Josiah also heard the Note … and fled from it to the world-in-law? Then he went on: “But what I’m going to say now is my own idea. Supposing that everything that happens on the one planet, the planet that we call Delusion, reacts

Clem,’ (for my stepmother’s name was Clementine), ‘I don’t trust you no further than I see you, but, for all that, you can turn me round your little finger, because I’m a silly, besotted old fool, and we both know it.’ Oh! I’ve always said that my poor father had both his eyes wide open, in spite of him being the slave of her pretty face. It was not that he didn’t see, or couldn’t see — what he lacked was the heart to speak out.” “Poor fellow! And now, Mistress Ivy, I think you should tell me

business was put a stop to once and for all, he’d have Pugwalker tarred and feathered, and make the neighborhood too hot for him to stay in it. And, I remember, I heard him hawking and spitting, as if he’d rid himself of something foul. And he said that the Gibbertys had always been respected, and that the farm, ever since they had owned it, had helped to make the people of Dorimare straight-limbed and clean-blooded, for it had sent fresh meat and milk to market, and good grain to the miller, and

Moongrass by now.” “To Moongrass?” And Luke stared at him in amazement. “Aye, to Moongrass, where the cheeses come from. You see it was this way. I’m goatherd to the Lud yeomanry what the Seneschal has sent to watch the border to keep out you know what. And who should come running into their camp about half an hour ago with his red jerkin and his green hair but your young gentleman. ‘Halt!’ cries the Yeoman on guard. ‘Let me pass. I’m young Master Chanticleer,’ cries he. ‘And where are you