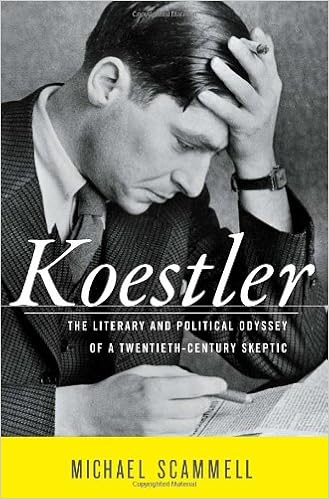

Koestler: The Literary and Political Odyssey of a Twentieth-Century Skeptic

Michael Scammell

Language: English

Pages: 720

ISBN: 0394576306

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

From award-winning author Michael Scammell comes a monumental achievement: the first authorized biography of Arthur Koestler, one of the most influential and controversial intellectuals of the twentieth century. Over a decade in the making, and based on new research and full access to its subject’s papers, Koestler is the definitive account of this fascinating and polarizing figure. Though best known as the creator of the classic anti-Communist novel Darkness at Noon, Koestler is here revealed as much more–a man whose personal life was as astonishing as his literary accomplishments.

Koestler portrays the anguished youth of a boy raised in Budapest by a possessive and mercurial mother and an erratic father, marked for life by a forced operation performed without anesthesia when he was five, growing up feeling unloved and unprotected. Here is the young man whose experience of anti-Semitism and devotion to Zionism provoked him to move to Palestine; the foreign correspondent who risked his life from the North Pole to Franco’s Spain, where he was imprisoned and sentenced to death; the committed Communist for whom the brutal truth of Stalin’s show trials inspired the superb and angry novel that became an instant classic in 1940. Scammell also provides new details of Koestler’s amazing World War II adventures, including his escape from occupied France by joining the Foreign Legion and his bluffing his way illegally to England, where his controversial novel Arrival and Departure, published in 1943, was the first to portray Hitler’s Final Solution.

Without sentimentality, Scammell explores Koestler’s turbulent private life: his drug use, his manic depression, the frenetic womanizing that doomed his three marriages and led to an accusation of rape that posthumously tainted his reputation, and his startling suicide while fatally ill in 1983–an act shared by his healthy third wife, Cynthia–rendered unforgettably as part of his dark and disturbing legacy.

Featuring cameos of famous friends and colleagues including Langston Hughes, George Orwell, and Albert Camus, Koestler gives a full account of the author’s voluminous writings, making the case that the autobiographies and essays are fit to stand beside Darkness at Noon as works of lasting literary value. Koestler adds up to an indelible portrait of this brilliant, unpredictable, and talented writer, once memorably described as “one third blackguard, one third lunatic, and one third genius.”

like himself, found it a “great joy to read,” and Eric Mills, the head of the Palestinian Immigration Office in Jerusalem, agreed that Koestler had written a book “of penetrative insight,” though his descriptions of British officials were “unfair.” “I do not think that you will be loved for the book.”18 As it turned out, the initial sex scene skewed much of the response to the novel, not because of its frankness but because it betrayed Koestler’s ideal of realism. Koestler claimed that Joseph’s

Safed, Tiberias, and several other towns where fighting had erupted. Driving down the coast to Tel Aviv, Koestler was also reminded of Spain. The road teemed with trucks and buses packed with singing soldiers. “In the open trucks they all stand upright holding on to each other, in the buses they sit on each other’s knees with elbows sticking out of the windows and their fists banging the rhythm of the song on the tin plating.” Recalling his hike down this empty coastal road twenty years earlier,

dissident named Andrei Kistyakovsky read Darkness at Noon for the first time and was galvanized into translating it for samizdat. Russia was still in pretty bad shape, wrote Kistyakovsky in his introduction. Russians desperately needed this book in order to understand their own past, and they could now read the novel “without risking their lives.”14 Koestler’s work still didn’t make it back to his native Hungary, however, even in samizdat. When George Mikes went to Budapest in 1979 and gave a

humiliation.” But death itself didn’t bother him. “Why should it? I don’t envisage a hell or purgatory. I think it’s conceivable that I will become a grain of salt in the ocean. I find that a pleasant prospect.”29 CHAPTER FORTY-EIGHT AN EASY WAY OF DYING If one could only use as much imagination planning one’s death as one used planning one’s life. —KOESTLER DIARY ENTRY AS KOESTLER APPROACHED his seventy-fifth year, he seemed finally to accept the consequences of old age. Perhaps he

Niebuhr, “To Moscow—and Back,” Nation, 1/28/50; Robert Hatch, “Studies in the Permanent Crisis,” New Republic, 3/19/50; Anonymous (Peter Calvocoresi), “Two-Way Rebellion,” Times Literary Supplement, 2/3/50. 18. Stranger, 75. 19. Phillips, 135–36; interview with Phillips, 10/10/92. 20. Danielle Hunebelle, “Portrait,” in Debray-Ritzen, 12–14. 21. Interview with Pamela Merewether, 3/8/90; Cynthia’s diary, 3/9/70, MS2305; “Auntie B” to Cynthia, 11/4/76, MS2390/2. 22. Interview with Betty