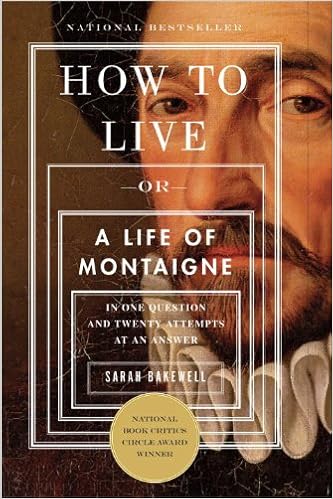

How to Live: Or A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer

Sarah Bakewell

Language: English

Pages: 416

ISBN: 1590514831

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

Winner of the 2010 National Book Critics Circle Award for Biography

How to get along with people, how to deal with violence, how to adjust to losing someone you love—such questions arise in most people’s lives. They are all versions of a bigger question: How do you live? This question obsessed Renaissance writers, none more than Michel Eyquem de Montaigne, considered by many to be the first truly modern individual. He wrote free-roaming explorations of his thoughts and experience, unlike anything written before. More than four hundred years later, Montaigne’s honesty and charm still draw people to him. Readers come to him in search of companionship, wisdom, and entertainment —and in search of themselves. Just as they will to this spirited and singular biography.

VII:320–2. 21 Epaminondas: II:36 694–6, I:42 229, II:12 415, and (for “in command of war itself”) III:1 738. See Vieillard-Baron, J.-L., “Épaminondas,” in Desan, Dictionnaire 330. 22 “Let us take away”: III:1 739. 23 Cruelly hating cruelty: II:11 379. Hatred of hunting: II:11 383. Chicken or hare: II:11 379. On Montaigne and cruelty, see Brahami, F., “Cruauté,” in Desan, Dictionnaire 236–8, and Hallie, P. P., “The ethics of Montaigne’s ‘De la cruauté,’ ”in La Charité, R. C. (ed.), O un amy!

Cameron and Willett (eds), Le Visage changeant de Montaigne 207–30. Montaigne: “Grotesques” and “Monstrous bodies”: I:28 164. Horace on poetry: Horace, Ars poetica 1–23. 7 Writing with rhythm of conversation: II:17 587. He speaks of his “langage coupé” in his instructions to the printer in the Bordeaux copy: see Sayce 283. 8 “Of a hundred members and faces”: I:50 266. 9 “Of Coaches”: III:6 831–49. On the title of this essay: see Tournon, A., “Fonction et sens d’un titre énigmatique,” Bulletin

the courtyard below, and probably in his room too, you were free to imagine the tower as a monastic cell, which Montaigne inhabited like a hermit. “Let us hasten to cross the threshold,” wrote one early visitor, Charles Compan, of the tower library: If your heart beats like mine with an indescribable emotion; if the memory of a great man inspires in you this deep veneration which one cannot refuse to the benefactors of humanity—enter. The pilgrimage tradition outlived the Romantic era proper.

French civil wars, in which transcendental extremism brought about subhuman cruelties on an overwhelming scale. The third “trouble” ended in August 1570, and a two-year peace ensued during the period when Montaigne lived on his estate and began work on the Essays. But, long before he had finished that work, the peace came to an abrupt and shocking end, with an event that could leave no one in doubt about the dark side of human nature. 12. Q. How to live? A. Guard your humanity TERROR

holes,” so as to form a shower so fine it was almost a mist. They carried on, getting ever closer to Rome. On the last day before reaching the city, November 3, 1580, Montaigne was so excited that, for once, he made everyone get up three hours before dawn to travel the last few miles. The road through the outskirts was not promising, all humps and clefts and potholes, but as they went on they glimpsed the first few ruins, and, at last, the great city itself. The thrill palled a little as they