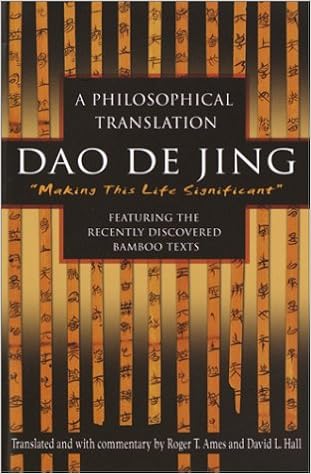

Dao De Jing: A Philosophical Translation

Roger T. Ames

Language: English

Pages: 256

ISBN: 0345444159

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

Composed more than 2,000 years ago during a turbulent period of Chinese history, the Dao de jing set forth an alternative vision of reality in a world torn apart by violence and betrayal. Daoism, as this subtle but enduring philosophy came to be known, offers a comprehensive view of experience grounded in a full understanding of the wonders hidden in the ordinary. Now in this luminous new translation, based on the recently discovered ancient bamboo scrolls, China scholars Roger T. Ames and David L. Hall bring the timeless wisdom of the Dao de jing into our contemporary world.

Though attributed to Laozi, “the Old Master,” the Dao de jing is, in fact, of unknown authorship and may well have originated in an oral tradition four hundred years before the time of Christ. Eschewing philosophical dogma, the Dao de jing set forth a series of maxims that outlined a new perspective on reality and invited readers to embark on a regimen of self-cultivation. In the Daoist world view, each particular element in our experience sends out an endless series of ripples throughout the cosmos. The unstated goal of the Dao de jing is self-transformation–the attainment of personal excellence that flows from the world and back into it. Responding to the teachings of Confucius, the Dao de jing revitalizes moral behavior by recommending a spontaneity made possible by the cultivated “habits” of the individual.

In this elegant volume, Ames and Hall feature the original Chinese texts of the Dao de jing and translate them into crisp, chiseled English that reads like poetry. Each of the eighty-one brief chapters is followed by clear, thought-provoking commentary exploring the layers of meaning in the text. The book’s extensive introduction is a model of accessible scholarship in which Ames and Hall consider the origin of the text, place the emergence of Daoist philosophy in its historical and political context, and outline its central tenets.

The Dao de jing is a work of timeless wisdom and beauty, as vital today as it was in ancient China. This new version will stand as both a compelling introduction to the complexities of Daoist thought and as the classic modern English translation.

language carries with it such an overlay of interpretation that, in the absence of reference to an extensive introduction and glossary, the philosophical import of the Chinese text is seriously compromised. Further, a failure of translators to be self-conscious and to take fair account of their own Gadamarian “prejudices” with the excuse that they are relying on some “objective” lexicon that, were the truth be known, is itself heavily colored with cultural biases, is to betray their readers not

as a process, but as a product. As a “way” that has already been laid, dao is stipulated and defined. This, then, is the objectified use of dao that would allow for the familiar demonstrative translation of the term dao as “the dao.” But to thus nominalize and conceptualize dao betrays its fluidity and reflexivity, and to give priority to that use is to take the first step in overwriting a process sensibility with substance ontology. We can neither step outside dao nor can we arrest its always

the center of the body and one’s source of equilibrium. The eye, on the other hand, is a major orifice through which the qi can leak away. The concern about insatiability is echoed in chapter 46, which says: There is no crime more onerous than greed, No misfortune more devastating than avarice. And no calamity that brings with it more grief than insatiability. Thus, knowing when enough is enough Is really satisfying. CHAPTER 13 “Favor and disgrace are cause for alarm.”

be, and once understanding is thus broadened, one’s thoughts will have integrity, and once one’s thoughts have integrity, the heart-and-mind will do what is proper, and once the heart-and-mind does what is proper, the person will be cultivated, and once the person is cultivated, families will have parity, and once families have parity, the state will be properly ordered, and once the state is properly ordered, there will be peace in the world. From the emperor down to the common folk, everything

Center. Dewey, John (1976–83). Middle Works, 1899–1924. 15 vols. Edited by Jo Ann Boydston. Carbondale, Ill.: Southern Illinois University Press. Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1883). Essays by Ralph Waldo Emerson. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company. Fukunaga Mitsuji (trans.) (1968). Roshi . Tokyo: Asahi Shinbunsha. Giles, Herbert A. (1886). The Remains of Lao Tzu. London: John Murray. Giradot, Norman J. (1983). Myth and Meaning in Early Taoism: The Theme of Chaos