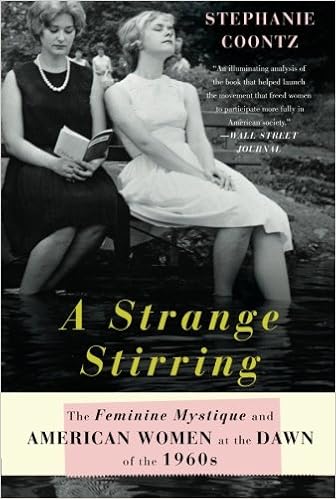

A Strange Stirring: The Feminine Mystique and American Women at the Dawn of the 1960s

Stephanie Coontz

Language: English

Pages: 256

ISBN: 046502842X

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

persuaded they had no other option. As one later told Fessler: “You couldn’t be an unwed mother.... If you weren’t married, your child was a bastard and those terms were used.” “Nobody ever asked me if I wanted to keep the baby, or explained the options,” said another. “I went to the maternity home, I was going to have the baby, they were going to take it, and I was going to go home. I was not allowed to keep the baby. I would have been disowned.” Before World War II, maternity homes had

Stern note, women’s “best opportunity to share in the wealth of their young male counterparts was to marry.” From 1951 to 1955, female full-time workers earned 63.9 percent of what male full-time workers earned. By 1963, women’s pay had fallen to less than 59 percent of men’s. Meanwhile, the proportion of women in high-prestige jobs declined: Fewer than 6 percent of working women held executive jobs in the 1950s. The experience of Sandra Day O’Connor illustrates the obstacles faced by women who

Union unless it trained women in needed defense fields such as engineering. By the beginning of the 1960s, politicians and employers agreed that both the economy and the political system needed more “woman power.” Most of the opinion-makers who supported expanding women’s participation in the economy expected that men would continue to organize and direct that woman power. Few envisioned an equal partnership at work or in government, much less at home. But the trend toward assigning status based

the dean than talking about Friedan’s ideas. Adams graduated, married, and went to work as a social welfare case-worker. In her eighth month of pregnancy, she quit her job to stay home. But a few years later, having just finished playing with her daughter, she began to vacuum the carpet. “All of a sudden, I heard this voice that said, ‘there’s more to life than this,’ and that meeting with the dean of women popped into my mind along with Betty Friedan and The Feminine Mystique .” Soon afterward

identical in all respects except gender and parental status and asked college students to evaluate and rank them. The students consistently rated the supposed mothers as less competent than the nonmothers. Applicants identified as mothers were 79 percent less likely to be offered jobs, and when hired, they were offered an average of $11,000 a year less in salary. The students also held the mothers to higher standards of performance and punctuality than women with identical résumés but no