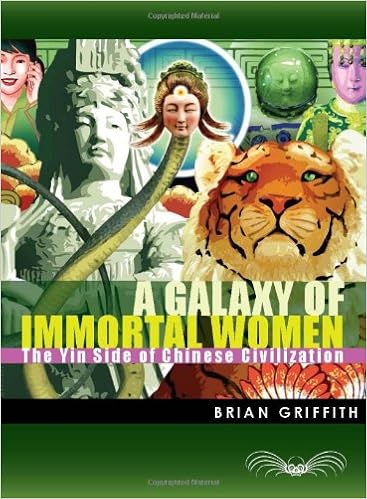

A Galaxy of Immortal Women: The Yin Side of Chinese Civilization

Brian Griffith

Language: English

Pages: 336

ISBN: 1935259148

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

“A valuable historical reference guide.” —Publishers Weekly

“This is a very ambitious and timely book, a book that many historians, literary theorists and story tellers who care about China and its “Other Half of the Sky” want to write, but Brian Griffith did it first, with such scope, ease and fun.” —WANG PING, author of The Last Communist Virgin and Aching for Beauty: Footbinding in China

“This book is a most engaging and entertaining read, and the depth of its scholarship is astounding. Griffith vividly describes the counterculture of Chinese goddesses, shows that their fascinating stories are alive and active today, and points us toward a more inclusive and caring partnership future.” —RIANE EISLER, author of The Real Wealth of Nations: Creating a Caring Economics and The Chalice and the Blade: Our History, Our Future

Touching on the whole story of China—from Neolithic villages to a globalized Shanghai—this book ties mythology, archaeology, history, religion, folklore, literature, and journalism into a millennia-spanning story about how Chinese women—and their goddess traditions—fostered a counterculture that flourishes and grows stronger every day.

As Brian Griffith charts the stories of China’s founding mothers, shamanesses, goddesses, and ordinary heroines, he also explores the largely untold story of women’s contributions to cultural life in the world’s biggest society and provides inspiration for all global citizens.

Brian Griffith grew up in Texas, studied history at the University of Alberta, and now lives just outside of Toronto, Ontario. He is an independent historian who examines how cultural history influences our lives, and how collective experience offers insights for our future.

Tibetan Buddhist master of the 1400s, recognized as the embodiment of the meditation deity Vajravarahi. Also known as Samding Dorje Pagmo, she began a line of female tulkus, or reincarnate lamas, which continues to the present. Chuang Mu (Ch’uang Mu, or Ch’ang Mu). The goddess of the bedroom and of sexual delights. Cinnabar Mother of Highest Prime. The imperial lady who resides in the third star of the Big Dipper constellation, who governs time and the six yin powers. Dagmema. The enlightened

Clarity; Dwelling in exile, I wandered the five marchmounts. Taking you, milord, as not bound by the common, I come here to urge you to divine transcendents’ studies. Even Ko Hung had a wife! The Queen Mother also had a husband! Divine transcendents all have numinous mates! What would you think of getting together, milord? (Cahill, 1993, 89) In China, probably most people felt that spirituality and sexuality were quite compatible, and even mutually reinforcing. The spiritual quest was

will be strengthened because the cows constantly tread on them; and the mulberry trees will grow beautifully because of the nourishing water” (Ebrey, 1981, 110). In the flooded rice fields, a symbiosis of fish, grass, rice, and algae produced the most efficient farming system in world history. The output of energy is about 50 times greater than the input (Ponting, 1991, 291–292). Naturally, the more successful this farming civilization grew, the more people it supported. And the greater the

a brilliant young official named Liu Qi, who happened to be the man reincarnated from the drowned vegetable seller. After a desperate struggle, Chen Jinggu was able to save him. The two promptly fell in love, and so the great shamaness married. The vegetable seller was granted his wish to marry the goddess, but only on the other side of death. Some time afterwards, the Kingdom of Min suffered a deadly drought, and Chen Jinggu was called as chief shaman to invoke rain. This ritual involved the

teachers, and spirit mediums. Besides, farming villagers were seldom interested in “renouncing the world.” They were more prone to worship deities of nature than to wish for salvation from the earthly realm. The Indian monastic practice of begging for alms was so repugnant to Chinese values, that the practice basically died out among China’s Buddhists (Hawkins, 2004, 240–241). To compete successfully in China, Buddhism had to change. And it did change, with almost amazing flexibility. One of the